View Camera PSF Measuring Part 1

There is a class all mechanical engineers at MIT have to take which is called 2.671 Instrument and Measurement. I have a lot of qualms with the class, but it does make the students do an interesting measurement and data analysis project called the “Go Forth and Measure”. People have measured silly things sports bra effectiveness by placing accelerometers on boobs or french fry bend radius, in addition to more technical things like propeller thrust efficiency and lens MTF. For my project, I wanted to do something with Bayley’s beautiful Sinar view camera. I took pictures at different intervals of focus pull and tilt to try to discover how small of a movement I needed to make in order for the sharpness (as defined by the FWHM of the PSF) to change imperceptibly.

View Camera

If you already know how view cameras work, skip this section.

For those who don’t know, view cameras are a special kind of camera generally referring to the lens being able to be moved relative to the sensor. You can do really awesome shots, such as non-parallel depths of field as seen in this picture of a laser:

As you can see, the whole front length of the laser is in focus, despite being diagonal to the observer. Additionally, the extra swing of the depth of field has created an extra buttery background.

How does it work? The lens and sensor position relative to each other can be controlled by a set of knobs. The knobs do the following:

- Focus Pull (move back and forth along the optical axis to change focal length)

- Shift (translate vertically or horizontally perpendicular to the optical axis, usually to correct for perspective shift)

- Tilt (rotate along the horizontal axis perpendicular to the optical axis, moving the depth of field)

- Swing (rotate along the horizontal axfis perpendicular to the optical axis, moving the depth of field)

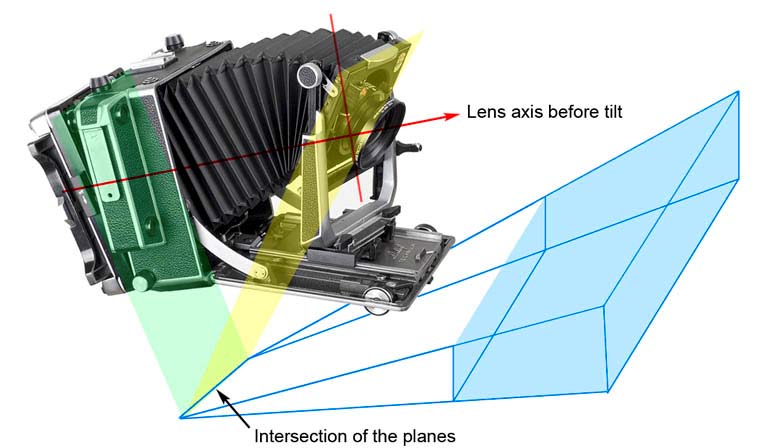

After moving each of these, the plane of focus is determined by Scheimpflug’s rule:

The subject plane is rendered sharp when the subject plane, the lens plane, and the focus plane all meet in a line.

We can illustrate this a bit better with a picture from Luminous Landscape:

You can read about view cameras even more to your heart’s content in this technical writeup.

The PSF and Sharpness

View cameras in practice are extremely difficult to focus perfectly. There’s no auto-focus or viewfinder, so the photographer has to rely on live view to focus it. Bayley’s Sinar view camera has an abysmal live view hooked up to a Macbook G4 that refreshes at ~1Hz, which means focusing can take hours. Even with a much faster live view using a Sony a6000 sensor (thanks to Ben Katz), focusing still takes tens of minutes. abandon all hope of taking razor-sharp photos of live subjects. So, for my “Go Forth and Measure” project, I decided to map the sharpness of Bayley’s camera to its movements, hopefully giving a good metric for how much knob twiddling is needed in order to get the darn thing in focus.

Cameras have fundamental limits of sharpness due to their lens’s resolving power sensor pixel size, and diffraction limits(see this post on Luminous Landscape). (Bayley tells me that the Schneider apo-componon f/4.5 50mm can’t quite resolve the Sony a6000 sensor, but shh don’t tell 2.671 that!). With this in mind, if I want to know how much a camera movement like tilt or focus pull affect sharpness, I should be able to find a sweet spot where moving the movement slightly doesn’t create a perceptible difference in sharpness, because of the circle of confusion.

What does sharpness mean in technical terms? Well, we can think of a nice measurement of sharpness being the point spread function (PSF), or a camera’s response to an impulse (a point light source). But it’s awfully hard to generate a point light source small enough to be perceived as such by a camera. You might need a laser or some other such thing. Let’s think of an easier measurement.

We could take the line spread function (LSF), or the system’s response to a line. Unfortunately, skinny lines are about as hard to generate as tiny points. But, the LSF is the derivative of the edge spread function (ESF), which we can obtain by getting a system response to a clean edge, such as a black and white edge in a photography test chart.

Technically this doesn’t perfectly characterize sharpness, as a line has orientation and would only capture one dimension of the PSF. Lenses and sensors have aberrations that make the PSF different in horizontal and vertical dimensions. But, for a rough measure of sharpness, we can assume that the PSF is radially symmetric, and therefore we only need the LSF and ESF in one orientation to characterize the PSF. Using the PSF, we can find the full width at half maximum (FWHM) value as a measure of sharpness, with smaller values of FWHM being sharper. For an ideal edge, the FWHM should be 1-4 pixels, meaning the edge is only a few pixels wide.

The Experiment

For the experiment, I took pictures at different intervals of focus pull and tilt to try to discover how small of a movement I needed to make in order for the sharpness (as defined by the FWHM of the PSF) to change imperceptibly. All the dirty details of how the experiment went down is in the paper I am writing here, to be replaced with the complete version instead of the draft it currently is.

The Results

Wait for the next post!